KEITH VAUGHAN – A REVIVAL?

By Christopher Andreae

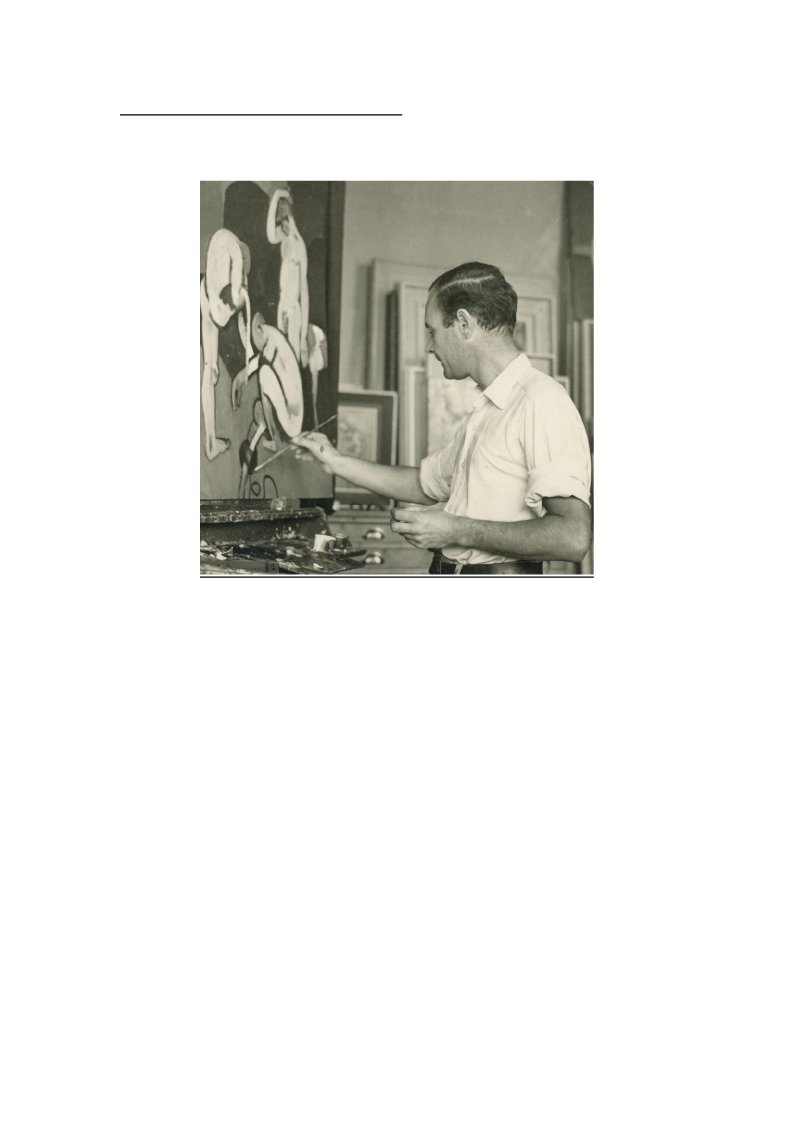

Keith Vaughan, Belsize Park, London, 1953, painting Second Assembly of Figures.

Photographer unknown.

(Hastings and Evans Collection)

It is just over 100 years since the English painter Keith Vaughan (1912 –

1977) was born. The male nude was his principal subject. But he was also

a powerful landscape painter.

He was self-taught, and evolved over a long career a style that was like

sculpture in paint – it was structured and bold, a build-up of a kind of

impassioned, angular patchwork of planes. His virtually always male,

vertical figures seem strangely isolated, sometimes like symbolic

mannequins. Or they interact but do so introspectively, as though each

figure is separately imprisoned within its own dream. Some groups of

figures are like shades or ghosts, spectral, haunting, movingly introverted

and sad. Then there are others that appear to be exerting or exercising

themselves with a sort of exuberant muscular bravado. The arms of a

statuesque figure stretch out horizontally and give him the air of a

classical discus thrower – or a crucified Christ.

Cover of Keith Vaughan by Philip Vann and Gerard Hastings published by

Lund Humphries in association with Osborne Samuel 2012. £40.

Angst is never far away, though any sort of consciously religious

connotations are certainly rare in his work. His figures often seem fraught

with mute longing for something unspecified – but it is not necessarily

going to be fulfilled. Crowded groups of figures, in a series painted over

many years, gather in what he called “assemblies.” Some of these figures

merge indistinguishably into each other in an almost abstract

conglomeration. Individuals can be completely lost in the mass.

Seventh Assembly of Figures (Nile Group) 1964 oil on canvas 122 x 137.5 cm by Keith

Vaughan. The Hargreaves and Bail Trust. Courtesy of Osborne Samuel

Certainly Vaughan is an original.

This centenary of his birth has provided useful opportunities to re-assess

and re-display Vaughan’s work and life. There have been revealing

exhibitions and books – deep and thorough looks at his (very complex)

character and the strength of his particular vision. In answer to suspicions

that he has been unfairly neglected, all this recent advocacy, discussion,

exposure and publishing activity adds up to a vigorous attempt at revival

– a revival driven by the ardent convictions of his admirers.

Whether or not it will place Vaughan higher up the scale of art-world

estimation remains to be seen. He has still stopped short of the ultimate

accolade of a full-scale retrospective at the Tate or any major art

institution, though he was given in his lifetime a major show at the

Whitechapel Art Gallery under Bryan Robertson’s directorship. The Tate

owns 13 of his works, admittedly, and also Vaughan’s extensive,

intensive journals are now housed in the Tate Archive. But, with one

exception, it has been up to private commercial galleries to stage recent

celebratory exhibitions, such as Osborne Samuel in London, in 2011 and

2012. This gallery’s catalogue for its 2011 and 2012 Vaughan exhibitions

can still be seen and read in full on line and amounts to an impressive

retrospective in itself. Anthony Hepworth Fine Art, London, and Bath,

held a show in 2012 of works on paper.

It was Pallant House Gallery in Chichester that was the only public

gallery to commemorate Vaughan’s birth – with an exhibition called

Keith Vaughan: Romanticism to Abstraction.

And now, at the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff (until November

24) is an exhibition of drawings, prints, book illustrations and

photographs under the title “Figure and Ground.” There is to be a second

showing of this exhibition from February 17 to March 28 2014 at the

Tessa Sidey Gallery, The School of Art, Aberystwyth University. Since

the show consists of highlights from the Keith Vaughan holdings housed

here, the works will, in effect, be returning home. There is a book

published to coincide with this exhibition which effectively prolongs its

Cover of Keith Vaughan, Figure and Ground, Drawings,

Prints and Photographs, edited by Colin Cruise.

Published by Sansom & Company Ltd 2013. £16.50

One of the new books about the artist, (“Keith Vaughan” published by

Lund Humphries) contains a lengthy, very considered and sympathetic

essay by Philip Vann on the intricate cross-currents of Vaughan’s

character and his work. The exclusive concentration, in his paintings, on

male figures, stems from his homosexuality, and it is today possible to be

open and frank about this (as Vaughan himself was in his exhaustive

journals). It was not always so, of course, as Vaughan noted: “It is

difficult to bear in mind that with all one’s honours, distinctions, success

etc. one remains a member of the criminal class. My sexual relationships,

on the rare occasions when they have been successful would, or could,

earn me at least life imprisonment if known & prosecuted.”

Vann adds to this: “His almost exclusive subject matter – the male nude –

was a daring, courageous if perhaps ultimately irresistible choice,

especially during the pre-1967 era (in Britain) and the pre-gay liberation

movement period . . . . when society seemed to be governed,

unchallenged, by what Christopher Isherwood called ‘the heterosexual

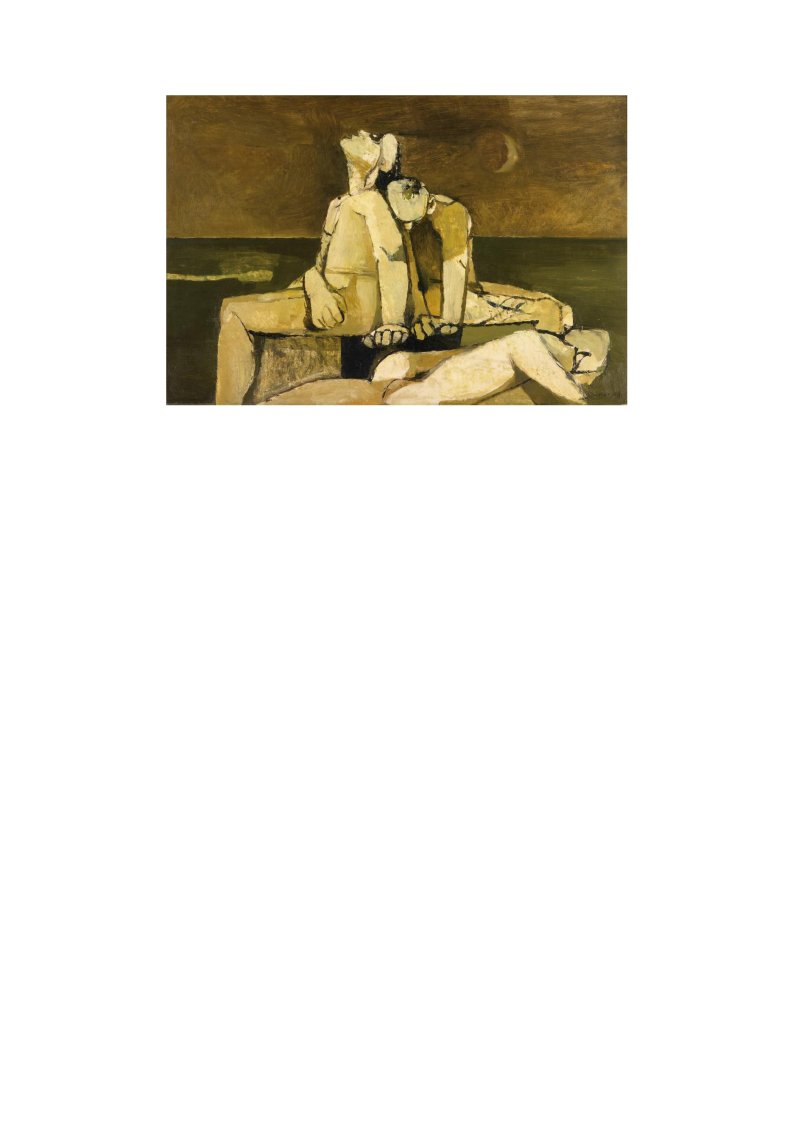

The Raft 1948 oil on cardboard 51 x 76 cm by Keith Vaughan. Private Collection. Courtesy of Osborne Samuel

Vaughan did not hide the appeal of the male body as his main interest and

theme, and he was critical of homosexual writers and artists who wrote

about or painted “women” when they really meant “men” even if this

subterfuge was perfectly understandable. Presumably he felt this

compromise was a cop-out. On the other hand, some critics of his work

accused him of his own sort of cop-out because they felt he sanitised his

male figures by obscuring their genitals. This is fairly preposterous when

you consider the constraints of the time in which he spent most of his

working life. There is, anyway, not the slightest doubt that his figures are

not female. His defence was along the lines that he deliberately made his

figures human rather than erotic. There is, however, an unspoken

assumption in this attitude that the male figure alone can epitomise

universal humanity – yet a comprehensive view of the human race and its

potential as art can hardly leave out “woman.”

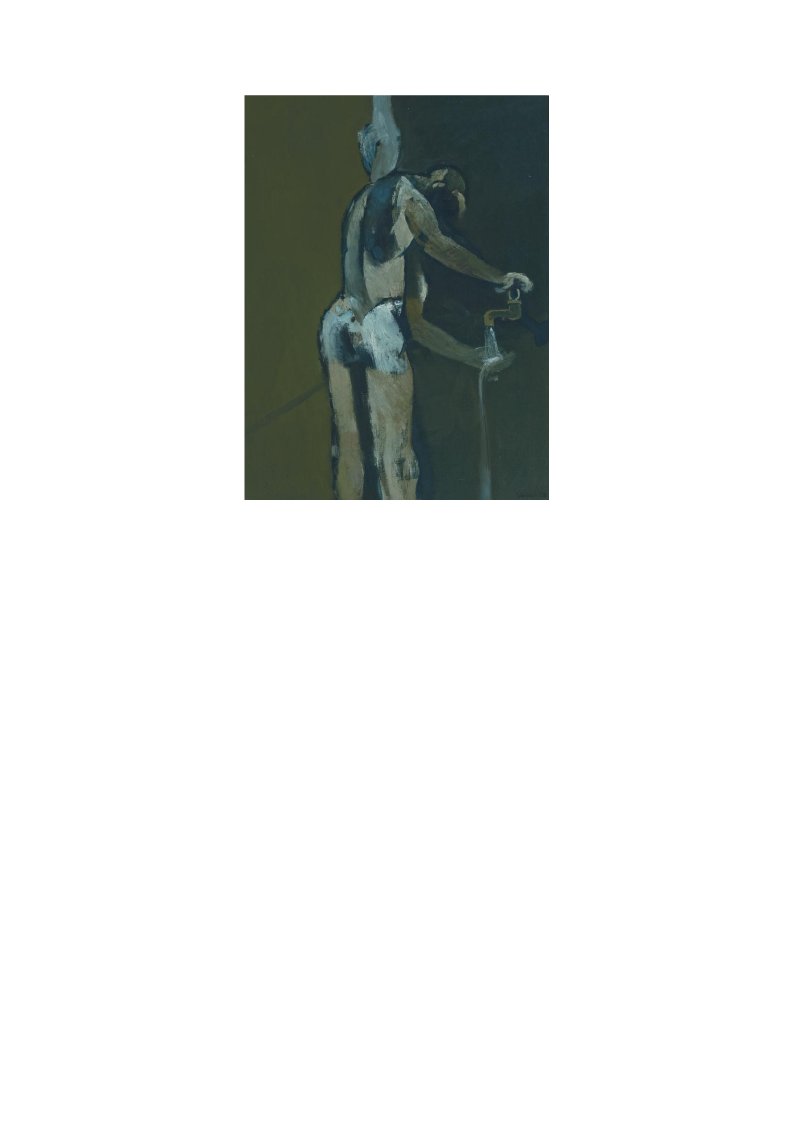

Nude Washing at Tap 1951 oil on canvas

83.8 x 63.5 cm by Keith Vaughan. Private Collection.

Courtesy of Osborne Samuel

Vann doesn’t agree with what he calls the “charges that Vaughan’s

paintings of the male nude are coyly evasive, wilfully opaque or furtively

prurient . . . .” Instead he returns “to Vaughan’s own statement that he

starts off by making the image of the human figure erotic (‘because that’s

the first thing that strikes you about it’)” but then “the erotic image soon

ceases to be human and you paint the eroticism out.” One problem with

this argument could be that while the male figure is to Vaughan himself

unmistakably erotic, to many others it doesn’t seem erotic at all. This is

not a matter of a deliberate “heterosexual dictatorship” for which there is

no justification. It is simple fact. The “eroticism” of the male nude is not

necessarily “the first thing that strikes” everyone.

Nevertheless, Vaughan’s paintings are inarguably powerful, charged,

monumental and sensual. His feelings are translated into vigorous paint

and memorably expressive imagery that are decidedly more potent than a

mere exposure of private emotion could be. The rigour of his paintings is

in essence the intimate and inward made outward and public. His

fascination with modern dance is a significant ingredient, his painted

figures performing with taut, energetic movements and gestures.

One possible reason that the Tate passed him by, is hinted at in an acerbic

comment in his journal at the time “pop art” surfaced, in the 1960s. Like

the abstract expressionists in the U.S. “serious” British artists like

Vaughan were affronted by the flippancy of this jokey new tendency. It

was, ironically, a significant exhibition staged by Bryan Robertson at the

Whitechapel Gallery two years after the Vaughan retrospective there, that

aroused his resentment – the ground-breaking “New Generation”

exhibition of 1964. It made Vaughan feel virtually extinct: “After all

one’s thought and search and effort to make some sort of image which

would embody the life of our time, it turns out that all that was really

significant were toffee wrappers, liquorice allsorts and ton-up motor bikes

. . . . I understand how the stranded dinosaurs felt.”

The art establishment, and of course the media, could not ignore the

vitality and wit and currency of so-called pop art. Inevitably this “new”

art would come to mean that some of the “old generation”, including

Vaughan, started to look dated and out of touch. (Bryan Robertson,

however, continued to believe in Vaughan’s art). It can’t have helped

that both Vaughan’s art and pop art were in reaction against the aftermath

of the war, though they reacted in opposite ways: toVaughan (whose

brother had been killed early in the war) those lost years cast a grim

shadow across the late forties and fifties. For all his originality and

experimentalism, it has been only too easy to categorise him as a

prominent figure “of his generation.” The youth culture in the sixties

turned away from the wartime and post-war heroism and privations by

celebrating – however facetiously or satirically – the lighter,

inconsequential side of life.

Yet Vaughan knew and admired David Hockney, for example, who was

surfacing at this time and was thought of as one of the pop artists. And

Hockney certainly benefitted from Vaughan’s example. Vaughan even

came some way, after a while, to understanding the character and

attraction of New York art, which he initially dismissed as “hollow.” (He

mentioned Rothko, who had been given a major show at the Whitechapel

in 1961.) The Tate, on the other hand, could once again not ignore the

shift from Paris to New York as the centre of the art world, and Vaughan

and the other post-war British artists were once more somewhat side-

Reclining Nude 1950 reworked 1958 and 1960

oil on canvas 86.3 x 119.4 cm. by Keith Vaughan. Private Collection.

Courtesy of Osborne Samuel

Another more contentious reason for Vaughan not being given the highest

honours might be that the homoerotic character of his work, however

much played down, may not have sat altogether comfortably with the

establishment at the Tate. This is only a guess, but if Bryan Robertson

had become the Tate director, this obviously would not have been any

sort of obstacle. However, in spite of his remarkable achievement at the

Whitechapel, politics and personal antipathy intervened and what would

have been an inspired choice of a Tate boss never occurred.

Theoretically there should be no difficulty today for the Tate to belatedly

consider a Vaughan exhibition. But it is interesting that the most recent

book of all published on Vaughan has radically broken what has, until

now, still remained something of a taboo.

Cover of Keith Vaughan The Photographs by Gerard Hastings

Published by Pagham Press 2013. £25.

“Keith Vaughan: The Photographs” by Gerard Hastings, published by

Pagham Press, goes further than before in displaying this aspect of

Vaughan’s work. The photographs in this book are certainly more explicit

than the images in his paintings. Vaughan himself let a few of his

photographs be seen. Philip Vann gives them close attention. But this

book, solely concentrated on his photographs, shows a number that have

never been seen in public before and strongly emphasises the importance

of his photographs to his paintings. Hastings makes the point that

Vaughan’s usual inhibitions disappeared when he was looking through a

camera lens. He quotes Vaughan’s close friend the artist Prunella Clough

as saying “Keith used the camera almost as a justification to look – really

look – at the male nude . . . . When Keith had a camera fixed to his eye, it

legitimised his gazing at another unclothed human being.”

Hastings mentions the fact that another friend of Vaughan, John Ball,

“had reservations about making Vaughan’s photographs public; he was

reluctant to reveal information concerning the artist’s visual sources . . . .”

(i.e. photographs). Given the long history of serious painters using

photography as source material this reservation seems strangely old-

fashioned. But more to the point, Ball’s “nervousness,” writes Hastings,

was also “related to the notion that eroticism, when centred on the male

(as opposed to the female) nude, is suspect in the public imagination . . .

.” He believed that homophobic attitudes still lingered. And he “was

concerned that autobiographical information, or content of a directly

sexual nature associated with Vaughan’s work, might diminish its

standing.” Clearly neither Vann nor Hastings has such qualms today. The

photographs, for all their homoeroticism, are no less informative as the

evidence of an essential part of Vaughan’s inspiration than any artist’s

sketchbooks, or the postcards pinned up on their studio walls.

_________

List of recent books on Keith Vaughan

Keith Vaughan, by Philip Vann and Gerard Hastings, 2012, published by

Lund Humphries in association with Osborne Samuel, £40

Keith Vaughan: The Mature Oils 1946 -1977, a commentary and a

catalogue raisonné, by Anthony Hepworth and Ian Massey, 2012, published

by Sansom & Company, £40

Cover of Keith Vaughan The Mature Oils 1946 – 1977

a commentary and a catalogue raisonné by Anthony Hepworth and Ian

Massey. Published by Sansom & Company Ltd 2012. £40

Drawing to a Close, The Final Journals of Keith Vaughan, by Gerard

Hastings, 2012, published by Pagham Press, 2012, £45

Cover of Drawing to a Close

The Final Journals of Keith Vaughan

By Gerard Hastings

Published by Pagham Press 2012 £45

Keith Vaughan: Figure and Ground, Drawings, Prints and Photographs,

edited by Colin Cruise, 2013, published by Sansom & Company, £16.50

Keith Vaughan: The Photographs by Gerard Hastings 2013, published by

Pagham Press, £25

Christopher Andreae is the author of Joan Eardley, 2012, published by

Lund Humphries